Beauty is an industry that understands the power of advertising. The creativity and artistry in some of the ads are more like art-house films, while some of the best known photographers in the industry are household names.

As the UK’s advertising regulator, the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) wants to see the industry continue to thrive and push the boundaries of creativity, but they should always strive to follow our rules to not mislead, cause harm or offence, or be socially irresponsible.

The ads that have strayed have been investigated by us and have faced negative media exposure for misleading consumers.

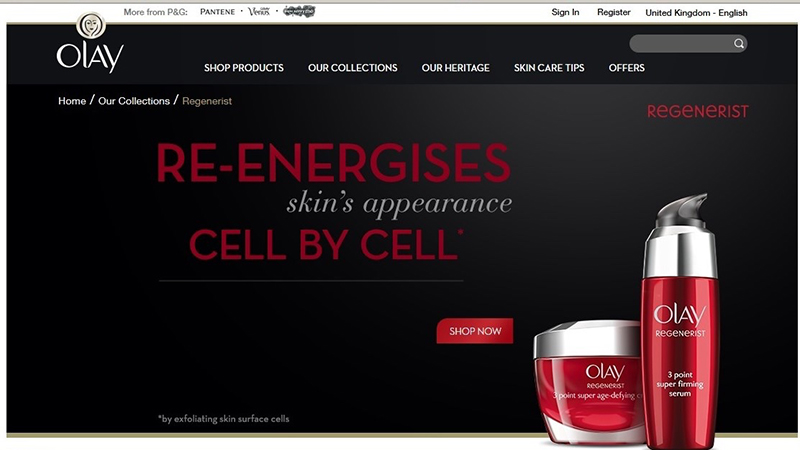

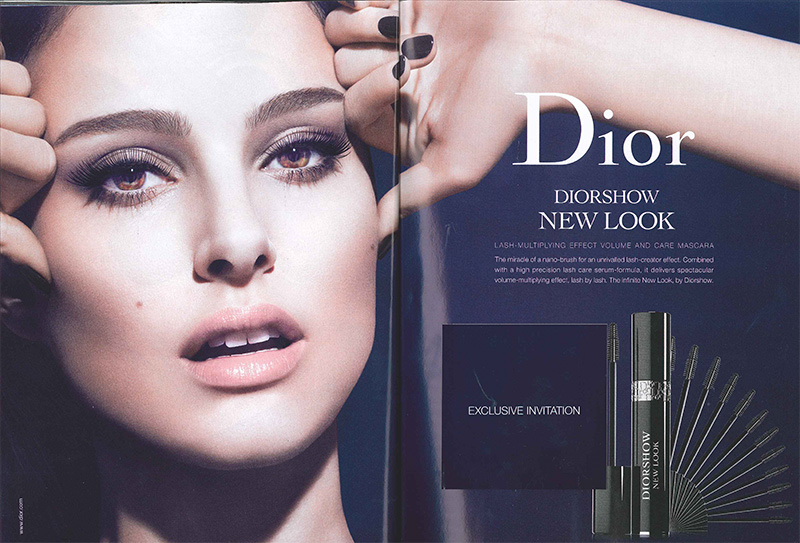

Coty’s Rimmel mascara ad featuring Cara Delevingne (2016), Clinique’s under-eye cream ad (2012), Olay Regenerist skin care (2016) and Dior’s mascara ad featuring Natalie Portman (2012) have all been banned by us.

Consumers must be able to trust the claims being made in ads about the benefits of using a particular product.

The overwhelming majority of beauty ads stick to our rules. However, the minority that we investigate and uphold complaints against tend to involve claims that are misleading and cannot be substantiated.

Always substantiate claims

In Olay Regenerist’s case, the ad claimed the product “Re-energises skin’s appearance cell by cell”. We considered that consumers would understand this claim to mean that the product would have a beneficial effect on the appearance of their skin, though it was not clear how that effect could be achieved.

We considered that it implied that the product would have a deeper physiological effect rather than only a surface level effect, and that the word ‘re-energises’ reinforced that impression in this context.

We understood that all products in the range contained niacinamide, which provided an exfoliation benefit. We considered that the results of the consumer perception test provided by Procter & Gamble indicated that a large proportion of users had perceived an improvement in their skin’s appearance after using Olay Regenerist 3 Point Age-Defying Night Cream.

They also provided survey results showing a high level of consumer agreement with the claim “Re-energises skin’s appearance cell by cell” in relation to different products in the Regenerist range.

However, we did not consider that an appearance benefit based only on the removal of surface cells was in line with the likely consumer interpretation of the claim in the context of the ad. We concluded that the claim had not been substantiated and was therefore misleading.

We are not saying pre- and post-production techniques can never be used in ads; for example, if an ad is for lipstick, it does not matter if the model is shown with eyelash inserts, brighter eyes or fine lines airbrushed out

Avoid post-production pitfalls

In Dior’s case, L’Oréal UK challenged whether a magazine ad for mascara, which showed an image of film star Natalie Portman, misleadingly exaggerated the likely effects of the product.

The headline in the ad stated “Diorshow New Look” and text stated “Lash-multiplying effect volume and care mascara. The miracle of a nano brush for an unrivalled lash creator effect. It delivers spectacular volume-multiplying effect, lash by lash”.

Dior told us that Portman was wearing mascara and eyeliner in the ad, but was not wearing any individual false lashes or a false set of eyelashes during the shoot and, accordingly, no eyelash inserts were used in pre-production.

However, we understood that there was digital retouching post-production which was intended to separate/increase the length and curve of a number of Portman’s lashes; to replace/fill a number of missing or damaged lashes; to increase the thickness and volume of a number of her natural lashes and, primarily, to stylistically lengthen and curve her lashes.

We considered that this post-production work was directly relevant to the apparent performance of the mascara product being advertised.

While we acknowledged that Dior had provided some before and after photos showing a model’s natural eyelashes and the effects of the product on her lashes, we had not seen evidence of the product’s effects on Portman’s lashes where there had not been any postproduction retouching.

We were concerned thatbwe had not seen evidence that the visual representation of the product’s effects on Portman’s lashes, as featured in the ad, could be achieved through use of the product only.

Because we had not seen sufficient evidence to show that the post-production retouching on Portman’s lashes in the ad did not exaggerate the likely effects of the product, we concluded the ad was likely to mislead.

Don’t exaggerate effects

In Coty’s case, we banned the TV ad for misleading consumers about the effect of the mascara because Cara Delevingne wore eyelash inserts and post-production techniques were used.

The ad conveyed a volumising, lengthening and thickening effect of the product that we considered was likely to exaggerate the effect beyond what could be achieved by consumers.

The beauty industry should be aware we are not saying pre- and post-production techniques can never be used in ads. For example, if an ad is for lipstick, it does not matter if the model is shown with eyelash inserts, brighter eyes or fine lines airbrushed out.

There are also some circumstances where it can be acceptable to use eyelash inserts for mascara ads. For example, we accept that where a model has damaged or missing eyelashes, inserts sometimes need to be used.

However, the inserts must be the same length as the model’s natural eyelashes; if they are longer, it will imply that the product has contributed to the long lashes and that is unfair on the consumer.

With regard to Clinique, a viewer challenged whether the TV ad was misleading because he believed the image of the model had been digitally manipulated and therefore misrepresented the results that the under-eye cream product could achieve.

The TV ad featured a voice-over which stated, “Seeing dark circles under the eyes? It can be fatigue, stress, age. And now, new Clinique Even Better Eyes takes eyes out of the shadows.”

Later, the model’s face was shown brightly lit against a bright white background, and the voice-over continued, “You see it instantly. Even Better Eyes.”

We understood that Clinique had carried out some digital re-touching on the image of the model in the ad, and that some of the retouching had been carried out on her eyes.

They had removed the veins from the whites of her eyes and made them whiter, altered the colour of her irises to make them darker and had removed the reflections and highlights in her irises.

We considered that the model’s eyes appeared brighter in the ‘after’ photo, compared to the ‘before’ photo, and that this was due to the postproduction techniques.

We said the ad must not be broadcast again in its current form. If advertisers require further information, we have free advice on our website.